If you attend the late service on Christmas Eve, the morning eucharist on Christmas day and this morning’s service, you will have heard the prologue to the Gospel of John three times by now. It is an awesome piece of writing — not just for the language with its gentle repetition but mostly because the thoughts contained therein are too marvelous for us to grasp.

Isn’t it amazing that in beginning, God created humankind and then breathed the breath of life, God’s presence, God’s shekina, into our souls and bodies? You and I share that essence of life, that which the Hebrew scriptures call nephesh, a word that cannot really be translated other than ‘essence of life.’ You and I share God’s presence in our very being, and you and I also share that animating breath of life that God has given us. You and I share that spark of life, the soul, which is the light that keeps us alive. It is amazing, isn’t it, that God, too, in Christ, shared the same?

Then there’s the wonderful language in the passage where it talks about the Word becoming flesh and ‘liv[ing] among us.’ The word translated as ‘lived’ means ‘tented,’ and it is the same word used in the Hebrew scriptures to describe God’s presence among the people: God is in the tent of the tabernacle; by the same token, Wisdom sets up her tent in our midst.

Eugene Peterson in his interpretation of the prologue to John puts this same phrase into a wonderful image: ‘The Word (otherwise called in his translation, ‘Word, the Incarnate One, as the Life-Light’) became flesh and blood, and moved into the neighborhood.’ What a fabulous way of expressing God’s proximity to us — God has moved into the neighbourhood — God is around every corner I turn, in every home I see and in every person. When I think of God dwelling with us in this way, I can’t help but remember the narrow alleys of the neighbourhood around Sma Trinidad near San Salvador or Soyapango where my friend Maura lives, with the 10000 people that lived crammed into that small neighbourhood. And there are the people who live right behind or around the corner from this church.

Mary Pratt in her poem, ‘Benedicite Around the Block’ (1) describes our neighbourhood well… a nun in a parking lot reading the daily office, a man in a brown suit and cowboy hat, a woman smoking a cigarette, a lawyer with a face like Atticus Finch (à la Gregory Peck), a woman tripping on high heels, a small boy with a duffle bag, the empty storefronts, leftover bits of trash, ‘rotting houses with rotting porches, wood fire escapes, littered with bottles in boxes and cans in bags, a broken shopping cart twisted in the cracked sidewalk.’

This is our ’hood. The people here are my brothers and sisters. They are your brothers and sisters. God is here in the neighbourhood, now, with us, in Jesus, in the Incarnation showing God’s love even when we cannot see it clearly.

Why does God move into our neighbourhood and midst? Patricia Wilson-Kastner captures not only the sense of divine Love that lies in the Incarnation but also some of the themes of the gospel of John when she writes:

‘Jesus became flesh so as to show forth the love of God among us, a love which is not merely an expression of good will, but the power of an energy which is the heart, core, and cohesive force of the universe…. Christ is the human expression of God to us, and thus we must try to understand what God meant in Christ…. Christ is… the one who shows all persons how to live. As a human he shows us what human self-possession and self-giving are. Thereby Christ shows us the link between divine and human, the cosmos and its conscious inhabitants.’ (2)

+

One of my favourite sights on Christmas Eve comes as the congregation lights its candles for the singing of Silent Night and the reading from the last gospel. There is something incredibly poignant and moving to see each one of your faces illuminated by a sole flickering flame, then multiplied by each candle. The congregation, as a whole, was still, listening to the proclamation of Christ coming into the world as the Light that enlightens the world. I saw you waiting for the light and, in your hands, as you held the light and with that little candle and its silly paper bobêche, that doesn’t do any good, you were holding hope.

As I looked at your illumined faces, I thought of the countless other people throughout the world and throughout time who have held a candle in their hands, hoping… hoping because something had happened or was going to happen to another part of humankind, God’s incarnation pitched amongst us.

Christmas Eve I saw faces lit by candles in the days after 9-11 as impromptu shrines sprang up, particularly around New York City. I saw faces lit by candles on a very cold March night in 2003 as 1000 of us stood on the steps to the state capitol building three days before the assault on Baghdad. I saw faces lit by candles in the days following the tsunami five years ago, people in Banda Aceh. I have seen photos of people holding candles, as a sign of silent protest outside of prisons when they know someone will be executed. I have seen candle upon candle in all the churches through which I passed on my 1570 kilometres of the Way of Saint James of Compostela. And on and on it goes, the universal human expression of sadness, community, seeking and mostly hope, united in our common humanity.

Why else would there be a website where you can light a virtual candle that will ‘burn’ for 48 hours?

When I checked their homepage in the writing of this sermon, it read: 12729 candles from 242 countries are shining.

The page then goes on to say:

In many different traditions lighting candles is a sacred action. It expresses more than words can express. It has to do with gratefulness. From time immemorial, people have lit candles in sacred places. Why should cyberspace not be sacred?

You may want to begin or end your day by the sacred ritual of lighting a candle on this website. Or you may want to light a birthday candle for a friend. One single guideline is all you need: Slow down and do it with full attention. From here on, you will be guided step by step. [gratefulness.org]

Yes, lighting a candle is a universal expression of seeking light and hope, of leaving a visible sign of an uttered prayer. It is why we have candles in the chapel by the icons of the Blessed Virgin Mary and John Henry Hopkins. You can always go there and light one. Those of us who pass by later may not know the content of your prayer nor who lit the candle but we will know that someone said a prayer and left behind a visual remembrance. And we will stop to look at that light, that prayer.

The symbol of light goes beyond simply hope or remembrance. It represents for us, in the eloquent words of John’s gospel, the Light that has come into the world, the Word, in other words, Jesus, God incarnate. God, Light, Jesus, with us. That is what we remember today.

+

God is with us, Emmanuel, and God will always be with us. We know where the story of the incarnation leads — it leads from the crib to the cross to the tomb and to the resurrection. While the resurrection may seem a long way off from Christmas, it is so deeply intertwined with Christmas as to be very close and present. It is the very hope upon which our faith stands.

Whether it is God pitching God’s tent amongst us, or dwelling in the neighbourhood, God in Christ is with us, loving us and showing us how to love one another. And God in Christ knows our struggles inside-out from birth to death. How comforting!

God continues to dwell among us in our neighbours, our companions on the way. Realise we are all different, but we are all of God and we are all icons of God’s light. Christ our brother dwells in us. Indeed, we have seen God’s glory, full of grace and truth. For that, let us give thanks.

END NOTES

(1) In Women’s Uncommon Prayers, eds. Elizabeth Geitz, Marjorie Burke, Ann Smith (Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing, 2000), 32-33.

(2) Patricia Wilson-Kastner, Faith, Feminism and the Christ (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983), Chapter 5, ‘Who Is This Christ?,’ 89-117.

The mission of Trinity's Communication Ministry is to spread the good news of God and Trinity Church to one another and in the community abroad. As news of our organization, ministries and other initiatives are well communicated through other means, it is the goal of this blog to share God's word through reflection of upcoming liturgical readings, special days on the Church calendar and other examples of our worship together.

Monday, December 28, 2009

Christmas Day sermon

Do you remember when you first got glasses? Or perhaps more recently when you first got bifocals? (It is hard to believe that I have been wearing them seven years.) It was a move that I had been dreading for years. Even though I see a lot better than I used to, there’s something about admitting to needing a stronger lens to be able to read that bugged me. Everyone warned me about the first few days of wearing the new glasses. Be careful going down or up stairs. Be careful opening doors. But the best advice was: Give yourself some time. Eventually your brain will adapt to this new way of seeing and eventually you’ll never think about the division in your lenses. You’ll see things in a new way.

My mind adapted after two months: it no longer stumbled at translating, as it were, at what I was seeing, or having to think about whether I should look out of the top or bottom lens (though these days, the altar book sometimes is a challenge which makes me wonder about trifocals!).

+

You’ll see things in a new way, the sage one said.

That’s what Christmas morning is all about, isn’t it?

Last night, with its darkness and the retelling of the intimate story so well known that we can practically recite it, gives way to the vast mystery that John’s prologue offers us, with the words we see inscribed on the frieze in front of us. For a short moment in time, we linger in that in-between place, that liminal place our faith invites us often to occupy.

It would be easier, really to stay at the side of that crib in a stable. But our faith seems not to let us stay too long in any one place. Just as Jesus was constantly on the move through his three short years of ministry, so God tugs at our hearts to keep us moving, to keep us alive.

All the while, God asks us to look at life, our faith and God in a new way. Most of all, God invites us to abide in the mystery of the incarnation and not be afraid of it.

We aren’t comfortable, really, about dwelling in mystery. How can we explain that flesh and God have joined hands? How can we explain that fear and hope coexist? We want answers, facts, straight-forward clear ideas.

But to seek that type of answer is to miss the glory of the incarnation. It’s to see it in the wrong way.

Ephrem the Syrian of the fourth century wrote of Christ in God: ‘It is right that human beings should acknowledge your divinity. It is right for the heavenly beings to worship your humanity. The heavenly beings were amazed to see how small you became, and earthly ones to see how exalted.’

Or as the Persian poet, Hafiz, said: ‘God looked where in the world he might display his face. He pitched his tent in human fields, no other place.’

How do we explain this paradox of God with us? We don’t, really. That is the beauty of mystery. There are some things in our life that surpass understanding. (Interestingly, not even the theological dictionaries try to explain ‘mystery.’ They let it stand as one component of our faith that doesn’t need words.)

Mystery… it is that holy place, that in-between space where the encounter transcends the effable, the speakable. The grace of mystery is that it makes possible what is unspeakable: that is, it incarnates the holy. Mysterium, sacramentum. Mystery is the encounter that transcends all of the limits of encounter, like love. Mystery is encounter. It is the truth, the reality of encounter. The Word was made flesh. What can we say? God become human, that human could become divine. What can we say?

Nothing. For when we truly encounter mystery, there are no words. Only silent awe. Only heartfelt thanks. Only silent tears that come from the depths of our heart.

Even as we struggle with these unfathomable thoughts, isn’t there also a part of us that doesn’t want the mystery to be completely explained? Certainly for me there is. I want to be lifted to that place before all time when God chose to love us, to create us and dwell in our midst. I want to touch that mystery every time we gather to break bread and share the cup. And I trust that when I do touch mystery, everything is all right.

What I know best of all, in the midst of all this mystery talk, is that God loves us.

As you celebrate the wonder of God’s gift of Christ, linger for a moment in the wonder of mystery. Let those wordless and unspeakable aspects of God’s love touch you as do the morning rays of sun that so often bathe us. And remember that unspeakable mystery that God has loved us from before the beginning and always will.

My mind adapted after two months: it no longer stumbled at translating, as it were, at what I was seeing, or having to think about whether I should look out of the top or bottom lens (though these days, the altar book sometimes is a challenge which makes me wonder about trifocals!).

+

You’ll see things in a new way, the sage one said.

That’s what Christmas morning is all about, isn’t it?

Last night, with its darkness and the retelling of the intimate story so well known that we can practically recite it, gives way to the vast mystery that John’s prologue offers us, with the words we see inscribed on the frieze in front of us. For a short moment in time, we linger in that in-between place, that liminal place our faith invites us often to occupy.

It would be easier, really to stay at the side of that crib in a stable. But our faith seems not to let us stay too long in any one place. Just as Jesus was constantly on the move through his three short years of ministry, so God tugs at our hearts to keep us moving, to keep us alive.

All the while, God asks us to look at life, our faith and God in a new way. Most of all, God invites us to abide in the mystery of the incarnation and not be afraid of it.

We aren’t comfortable, really, about dwelling in mystery. How can we explain that flesh and God have joined hands? How can we explain that fear and hope coexist? We want answers, facts, straight-forward clear ideas.

But to seek that type of answer is to miss the glory of the incarnation. It’s to see it in the wrong way.

Ephrem the Syrian of the fourth century wrote of Christ in God: ‘It is right that human beings should acknowledge your divinity. It is right for the heavenly beings to worship your humanity. The heavenly beings were amazed to see how small you became, and earthly ones to see how exalted.’

Or as the Persian poet, Hafiz, said: ‘God looked where in the world he might display his face. He pitched his tent in human fields, no other place.’

How do we explain this paradox of God with us? We don’t, really. That is the beauty of mystery. There are some things in our life that surpass understanding. (Interestingly, not even the theological dictionaries try to explain ‘mystery.’ They let it stand as one component of our faith that doesn’t need words.)

Mystery… it is that holy place, that in-between space where the encounter transcends the effable, the speakable. The grace of mystery is that it makes possible what is unspeakable: that is, it incarnates the holy. Mysterium, sacramentum. Mystery is the encounter that transcends all of the limits of encounter, like love. Mystery is encounter. It is the truth, the reality of encounter. The Word was made flesh. What can we say? God become human, that human could become divine. What can we say?

Nothing. For when we truly encounter mystery, there are no words. Only silent awe. Only heartfelt thanks. Only silent tears that come from the depths of our heart.

Even as we struggle with these unfathomable thoughts, isn’t there also a part of us that doesn’t want the mystery to be completely explained? Certainly for me there is. I want to be lifted to that place before all time when God chose to love us, to create us and dwell in our midst. I want to touch that mystery every time we gather to break bread and share the cup. And I trust that when I do touch mystery, everything is all right.

What I know best of all, in the midst of all this mystery talk, is that God loves us.

As you celebrate the wonder of God’s gift of Christ, linger for a moment in the wonder of mystery. Let those wordless and unspeakable aspects of God’s love touch you as do the morning rays of sun that so often bathe us. And remember that unspeakable mystery that God has loved us from before the beginning and always will.

Christmas Eve sermon

A fearsome and awesome event is happening tonight, something so awesome that we should be struck mute by it. Only a chorus of stones cries out in the stillness and silence the marvel that is taking place in our world, the birth of our Saviour Jesus Christ.

In the stillness and darkness of the night, inside this church, we gather to celebrate with joy and awe the coming of God amongst us. This coming is so amazing that words fail us… as they should. Yet we try to speak of the unspeakable because that is why we are here tonight.

In the form of a child, God comes to humanity. Jesus — the crossroads where God’s descending road and humanity’s ascending road meet — the bearer of hope, the redeemer and reconciler of us all, our saviour, comes to us tonight as a vulnerable child. In this child we find our hope, something that at times can be as fragile and vulnerable as a child.

And so tonight there are two things about the nativity story that I would like to emphasise: first, the larger, total meaning of Jesus’ birth and how we respond to it; and second, the gifts of Christ’s birth.

+

The words of Isaiah that we hear tonight — the most famous of all messianic prophecies — speak of the irrepressible hope of the people of Israel. The prophet declares that God has shed God’s light on the people of Israel. The nation has grown; its joy has increased. Now there is a child that is born who will free the people from want, from oppression and who will give the people an era of peace, justice and righteousness. A new king will be enthroned and this king will save the people. The prophecy of Isaiah speaks to the hope that the people have for something new.

Christian interpretation layered on top of Isaiah’s words turns the prophecy into one about the coming of Christ. The words ‘For unto us a child is born’ — words that many associate with a long ascending series of sixteenth notes in Handel’s Messiah — now are understood as suggesting the birth at Bethlehem, rather than the enthronement of a king. In the nativity, Jesus comes first in great humility but this is in anticipation of his coming again in majesty and glory.

It is this point that is crucial to our understanding of Christmas. There is more to Christmas than a baby in a crib in a stable. For we stay but a moment at the crib before moving on. What happens at the nativity that we remember tonight is but the beginning of the complete coming of Christ, and the whole of God’s saving act in Christ. Christ is God turned to us in grace and salvation. We remember at the crib the cross and the resurrection as well because that is the mystery of the Incarnation which we celebrate tonight.

Christmas calls a community back to its origins by remembering Jesus’ own beginnings as a human child, a prophet of God’s reign. What the church celebrates during this season is not primarily a birthday, but the beginning of a decisive new phase in the tempestuous history of God’s hunger for human companions.… Christmas does not ask us to pretend we are back in Bethlehem, kneeling before a crib; it asks us to recognize that the soft wood of the crib became the hard wood of the cross. 1

Archbishop Oscar Romero on Christmas Eve 1977 preached: ‘On this night, as every year for twenty centuries, we recall that God’s reign is now in this world and that Christ has inaugurated the fullness of time. Christ’s birth attests that God is now marching with us in history, that we do not go alone. With Christ, God has injected himself into history. With the birth of Christ, God’s reign is now inaugurated in human time.’ 2

That is an awful lot to lay on top of a small baby! But that is what this night is all about: the beginning of God’s reign in our time. There is something unspeakably wondrous about this — God-with-us, Jesus the Christ, is a holy mystery.

+

We come tonight to this place of mystery for many different reasons. Some come because this night means so much to us for memories. Some come for solace. Some come because it just seems the right thing to do. It would appear that we human beings are hard-wired for faith. Margaret Wente, self-professed agnostic, surprises herself to find that she needs to go to church on Christmas Eve. She writes about her faith instinct: ‘[Faith] bind[s] people together through collective rituals so that they can take collective action. There is no church of oneself.’ And so she goes to church on Christmas Eve, ‘to pay homage to the importance of tradition and continuity, and to experience the extraordinary power and solace and comfort of community.’ 3

Today’s opinion piece in the Rutland Herald expands upon this innate drive to come to church at Christmas: ‘The emotional power of the day derives from the fundamental simplicity of its meaning. The birth of a child among humble people in a barn long ago, the emergence of the child as the embodiment of the holy — what parents haven’t seen in their child’s birth a miracle of simplicity and of possibility, not that their baby will become the Messiah, but that he or she embodies the human in all its potential?’

Certainly the mystery of the incarnation, God-made-flesh in all of us, manifested itself Tuesday at the Gift of Life blood drawing at the Paramount, which once again broke the New England record for a single day drawing with 1024 pints taken in. As I gave, I looked across the stage at some sixty or so other donors, recognising that the life-blood that flows through them is the same as that which flows through me and, most incredibly, flowed through Jesus. That God could willingly become part of us, in the form of an infant, Jesus, defies words. It is mystery. And this realisation brings about wonder.

Indeed, in the words of the Herald, ‘Christmas becomes about … [an] atmosphere of wonderment and joy…. It is a great gift, better than toys, to awaken the wonder and to convey the love that should surround every[one]. The material gifts can be simple if those other gifts abound.’ 4

+

But there are more immaterial spiritual gifts than simply wonderment and joy that we receive from this holy birth. We also receive peace, completeness and hope, and the promise that divine salvation has entered the world. The hope of peace and salvation — that is what we celebrate at Christmas! The hope of peace and salvation — that is what brings us here tonight!

Humans long for peace, for justice, for something holy, for something far from earth’s realities, which we all can list by heart. We can have such a hope, not because we ourselves are able to construct the realm of happiness that God’s holy words proclaim but because the builder of a reign of justice, of love, and of peace is already in the midst of us. 5

‘We must be men and women of ceaseless hope, because only tomorrow can today’s human and Christian promise be realized; and every tomorrow will have its own tomorrow, world without end. Every human act, every Christian act, is an act of hope.’ 6

And what is this hope of which we speak tonight?

Hope is not optimism.

Hope is a very different thing. It is rooted in trust. It is grounded in a truth much larger than the unpredictable events of our lives.

Hope, says the writer of the Book of Hebrews, is the evidence, the security of things that are not yet seen, not yet experienced, not yet in hand.

Hope is what sustains us when facing the death of one we love; when passing through dark times in our life; when trying to maintain a heart of compassion in a world of endless violence.

Hope is what gives us time and patience when we struggle to understand life, and our future and God.

Hope is what helps us to heal, physically and spiritually, and what helps us to endure the time it takes to find new life.

Hope is what holds us when we have been betrayed or hurt by someone. Hope is what helps us to get up in the morning when the prospects for our life are dim and disappointing. Hope is what helps us face old age and death.

Hope is the energy that keeps us gentle and loving, reaching out far beyond our capacities with care and solidarity for others. Hope is not dependent on day-by-day experiences; rather it depends on God.

Hope is a gift. This gift is always looking for the small crack in our heart where it may find entry.

Hope is rooted in God’s never failing love, in trust and confidence that God will never, ever abandon us. People might abandon us; history might; life at times might. But never God!

Christmas, thus, is the celebration of a very human faith becoming hope. Faith-hope lies in tenderness, play, good will, and life.

May the Christ child whom you meet tonight grace you with the faith and hope that will accompany you this Christmas-tide and always. May the Christ child gift you the gift of joy and wonder in all God’s works. And may you be blessed this Christmas Eve and always.

END NOTES

1 Adapted from Nathan Mitchell (CSB, 31) and Leonardo Boff.

2 Archbishop Oscar Romero, Christmas 1977.

3 http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/opinions/when-in-doubt-an-atheists-christmas/article1406082/--/

4 http://www.rutlandherald.com/article/20091224/OPINION01/ 912240336/1038/OPINION01

5 Romero, 25.12.1977

6 Walter Burghardt…

In the stillness and darkness of the night, inside this church, we gather to celebrate with joy and awe the coming of God amongst us. This coming is so amazing that words fail us… as they should. Yet we try to speak of the unspeakable because that is why we are here tonight.

In the form of a child, God comes to humanity. Jesus — the crossroads where God’s descending road and humanity’s ascending road meet — the bearer of hope, the redeemer and reconciler of us all, our saviour, comes to us tonight as a vulnerable child. In this child we find our hope, something that at times can be as fragile and vulnerable as a child.

And so tonight there are two things about the nativity story that I would like to emphasise: first, the larger, total meaning of Jesus’ birth and how we respond to it; and second, the gifts of Christ’s birth.

+

The words of Isaiah that we hear tonight — the most famous of all messianic prophecies — speak of the irrepressible hope of the people of Israel. The prophet declares that God has shed God’s light on the people of Israel. The nation has grown; its joy has increased. Now there is a child that is born who will free the people from want, from oppression and who will give the people an era of peace, justice and righteousness. A new king will be enthroned and this king will save the people. The prophecy of Isaiah speaks to the hope that the people have for something new.

Christian interpretation layered on top of Isaiah’s words turns the prophecy into one about the coming of Christ. The words ‘For unto us a child is born’ — words that many associate with a long ascending series of sixteenth notes in Handel’s Messiah — now are understood as suggesting the birth at Bethlehem, rather than the enthronement of a king. In the nativity, Jesus comes first in great humility but this is in anticipation of his coming again in majesty and glory.

It is this point that is crucial to our understanding of Christmas. There is more to Christmas than a baby in a crib in a stable. For we stay but a moment at the crib before moving on. What happens at the nativity that we remember tonight is but the beginning of the complete coming of Christ, and the whole of God’s saving act in Christ. Christ is God turned to us in grace and salvation. We remember at the crib the cross and the resurrection as well because that is the mystery of the Incarnation which we celebrate tonight.

Christmas calls a community back to its origins by remembering Jesus’ own beginnings as a human child, a prophet of God’s reign. What the church celebrates during this season is not primarily a birthday, but the beginning of a decisive new phase in the tempestuous history of God’s hunger for human companions.… Christmas does not ask us to pretend we are back in Bethlehem, kneeling before a crib; it asks us to recognize that the soft wood of the crib became the hard wood of the cross. 1

Archbishop Oscar Romero on Christmas Eve 1977 preached: ‘On this night, as every year for twenty centuries, we recall that God’s reign is now in this world and that Christ has inaugurated the fullness of time. Christ’s birth attests that God is now marching with us in history, that we do not go alone. With Christ, God has injected himself into history. With the birth of Christ, God’s reign is now inaugurated in human time.’ 2

That is an awful lot to lay on top of a small baby! But that is what this night is all about: the beginning of God’s reign in our time. There is something unspeakably wondrous about this — God-with-us, Jesus the Christ, is a holy mystery.

+

We come tonight to this place of mystery for many different reasons. Some come because this night means so much to us for memories. Some come for solace. Some come because it just seems the right thing to do. It would appear that we human beings are hard-wired for faith. Margaret Wente, self-professed agnostic, surprises herself to find that she needs to go to church on Christmas Eve. She writes about her faith instinct: ‘[Faith] bind[s] people together through collective rituals so that they can take collective action. There is no church of oneself.’ And so she goes to church on Christmas Eve, ‘to pay homage to the importance of tradition and continuity, and to experience the extraordinary power and solace and comfort of community.’ 3

Today’s opinion piece in the Rutland Herald expands upon this innate drive to come to church at Christmas: ‘The emotional power of the day derives from the fundamental simplicity of its meaning. The birth of a child among humble people in a barn long ago, the emergence of the child as the embodiment of the holy — what parents haven’t seen in their child’s birth a miracle of simplicity and of possibility, not that their baby will become the Messiah, but that he or she embodies the human in all its potential?’

Certainly the mystery of the incarnation, God-made-flesh in all of us, manifested itself Tuesday at the Gift of Life blood drawing at the Paramount, which once again broke the New England record for a single day drawing with 1024 pints taken in. As I gave, I looked across the stage at some sixty or so other donors, recognising that the life-blood that flows through them is the same as that which flows through me and, most incredibly, flowed through Jesus. That God could willingly become part of us, in the form of an infant, Jesus, defies words. It is mystery. And this realisation brings about wonder.

Indeed, in the words of the Herald, ‘Christmas becomes about … [an] atmosphere of wonderment and joy…. It is a great gift, better than toys, to awaken the wonder and to convey the love that should surround every[one]. The material gifts can be simple if those other gifts abound.’ 4

+

But there are more immaterial spiritual gifts than simply wonderment and joy that we receive from this holy birth. We also receive peace, completeness and hope, and the promise that divine salvation has entered the world. The hope of peace and salvation — that is what we celebrate at Christmas! The hope of peace and salvation — that is what brings us here tonight!

Humans long for peace, for justice, for something holy, for something far from earth’s realities, which we all can list by heart. We can have such a hope, not because we ourselves are able to construct the realm of happiness that God’s holy words proclaim but because the builder of a reign of justice, of love, and of peace is already in the midst of us. 5

‘We must be men and women of ceaseless hope, because only tomorrow can today’s human and Christian promise be realized; and every tomorrow will have its own tomorrow, world without end. Every human act, every Christian act, is an act of hope.’ 6

And what is this hope of which we speak tonight?

Hope is not optimism.

Hope is a very different thing. It is rooted in trust. It is grounded in a truth much larger than the unpredictable events of our lives.

Hope, says the writer of the Book of Hebrews, is the evidence, the security of things that are not yet seen, not yet experienced, not yet in hand.

Hope is what sustains us when facing the death of one we love; when passing through dark times in our life; when trying to maintain a heart of compassion in a world of endless violence.

Hope is what gives us time and patience when we struggle to understand life, and our future and God.

Hope is what helps us to heal, physically and spiritually, and what helps us to endure the time it takes to find new life.

Hope is what holds us when we have been betrayed or hurt by someone. Hope is what helps us to get up in the morning when the prospects for our life are dim and disappointing. Hope is what helps us face old age and death.

Hope is the energy that keeps us gentle and loving, reaching out far beyond our capacities with care and solidarity for others. Hope is not dependent on day-by-day experiences; rather it depends on God.

Hope is a gift. This gift is always looking for the small crack in our heart where it may find entry.

Hope is rooted in God’s never failing love, in trust and confidence that God will never, ever abandon us. People might abandon us; history might; life at times might. But never God!

Christmas, thus, is the celebration of a very human faith becoming hope. Faith-hope lies in tenderness, play, good will, and life.

May the Christ child whom you meet tonight grace you with the faith and hope that will accompany you this Christmas-tide and always. May the Christ child gift you the gift of joy and wonder in all God’s works. And may you be blessed this Christmas Eve and always.

END NOTES

1 Adapted from Nathan Mitchell (CSB, 31) and Leonardo Boff.

2 Archbishop Oscar Romero, Christmas 1977.

3 http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/opinions/when-in-doubt-an-atheists-christmas/article1406082/--/

4 http://www.rutlandherald.com/article/20091224/OPINION01/ 912240336/1038/OPINION01

5 Romero, 25.12.1977

6 Walter Burghardt…

Christmas at Trinity

Here are just a couple of photographs of the church and chapel just before Christmas.

The chapel was set up Christmas Eve afternoon for a baptism.

Often by the icons of John Henry Hopkins and the Blessed Virgin Mary, one finds a lit candle, a symbol of prayer.

The church ready for Christmas Eve.... taken in the morning of the 24th.

Though a little blurry, the photo shows the high altar with its lace frontal.

The photos are all a bit light-struck but at least it was sunny and clear Christmas Eve!

The chapel was set up Christmas Eve afternoon for a baptism.

Often by the icons of John Henry Hopkins and the Blessed Virgin Mary, one finds a lit candle, a symbol of prayer.

The church ready for Christmas Eve.... taken in the morning of the 24th.

Though a little blurry, the photo shows the high altar with its lace frontal.

The photos are all a bit light-struck but at least it was sunny and clear Christmas Eve!

Sunday, December 20, 2009

Advent 4C

It seems as though the closer we get to Christmas, the more familiar the texts get. This morning we hear a passage from the gospel of Luke that is particularly dear…. Mary’s proclamation of God’s might and love in the hymn we call the Magnificat, known by its first Latin word which means ‘proclaims.’

Even before spending fourteen-plus years at a church called Saint Mary’s, the Magnificat had a special place in my heart. More than twenty years ago at Trinity, Princeton, a small group of us used get together early Wednesday morning to pray Morning Prayer in Spanish. We always used to say the Magnificat because it seemed to connect us with the peoples of Central and South America and their struggles. Even now I can begin the Magnificat in Spanish — Proclama mi alma la grandeza del Señor…. Now, all these years and experiences later, the song continues to grow in its personal associations.

But, in fact, the Magnificat — a canticle that we say or sing usually at Evening Prayer, a hymn that one hears in a traditional Lessons and Carols on Christmas Eve — is a radical hymn. In one of those great paradoxes of our tradition, this hymn that is so well-known for its beauty is also underestimated for its force.

The Magnificat praises the power, the holiness and the mercy of God, the God whom Mary calls Lord and Saviour. It does not appear to tell her story, the one we so often hear of the young virgin who humbly and obediently submits to God’s desire that she be the bearer of the Son of the Most High.

Or does it tell her story? Does it give us a different picture of Mary, a picture often lost behind the imagery of a young girl, a virgin who knows her lowly place?

+

Only Matthew and Luke relate stories of the birth of Jesus, and only Luke tells us that Mary was actually informed of God’s intentions. Interestingly, after all the erudite language of the beginning of the gospel of Luke, when we get to the Magnificat, the language shifts — as though we were to go from using Elizabethan to conversational English. Also, unlike all the historical detail that we heard in the events surrounding the arrival of John the Baptist, historical accuracy is strangely lacking from Luke’s description of the encounter between Mary and Elizabeth. He moves from the realm of historical reporting to telling a story imbued with mystery and wonder.

As a sign that ‘nothing will be impossible with God,’ the angel Gabriel tells Mary about the pregnancy of her barren relative, Elizabeth. The angel departs, and Mary hurries off to Elizabeth, whose child, John the Baptist, leaps in her womb at the sound of Mary’s voice. Elizabeth blesses Mary as the mother of her Lord and for her faith in the truth of the message she has heard. Mary responds to Elizabeth with the words of the Magnificat: ‘My soul magnifies the Lord, and my Spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, for God has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant. Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed, for the Mighty One has done great things for me, and holy is God’s name….’

This rare New Testament psalm of praise can be divided into three parts: first, a personal thanksgiving for God’s actions for Mary; second, praise for God’s acts to all, and third, praise for God’s acts for the people of Israel.

Mary’s praise comes from deep within; her soul extols God her Saviour, the God who brings not only her but Israel out of bondage into right relationship with one another and with God. God the Mighty One will raise up those who are cast down and nourish those who are starving. She then considers God’s mercy — that loyal, faithful, gracious love that God has had in covenant with God’s people throughout time. The Magnificat itself is remarkable as a hymn of praise that is full of joy for God’s actions. It seems so fitting that the God-bearer, Mary, should be the one to proclaim these words even as she stands on the turning point of the ages.

+

The power of Mary’s words that always shake me to my roots and make me question how well I am doing as a follower of Jesus, her son. If I pray the Magnificat, verse by verse, and imagine myself in Mary’s place, how do these verses resonate within my heart? So, walk with me for a moment in a reflection on this hymn.

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour; *

for you have looked with favor on your lowly servant.

How well do I proclaim God’s greatness? Even in those moments of uncertainty, when it seems that God is asking me to do something impossible, when life seems to be asking too much of me, is my spirit able to rejoice honestly, openly, truly, thankfully in God my saviour?

From this day all generations will call me blessed: *

the Almighty has done great things for me, and holy is your Name.

How well am I able to acknowledge the great things that God has done for me, and praise God’s holy name? When things seem to be too much, am I still able to praise God? (I always think of the story of a homeless woman in Boston, who still prays every morning: Thank you, God, because I woke up this morning.)

You have mercy on those who fear you *

in every generation.

Do I recognise the mercy God has had upon me? How God has forgiven me the wrongs I have done, the wrongs I still do, and the pardon extended to me that will always be there even before I ask? Can I recognise that that same mercy is extended to others, even those with whom I am still not in right relationship? Can I give thanks that God’s mercy is there for all?

You have shown the strength of your arm, *

you have scattered the proud in their conceit.

How honest am I in acknowledging that I, too, am one of the proud? When do I need to be taken down a peg or two? When do I need to be knocked off my high horse of self-righteousness? When do I acknowledge that, in the words of James Wendon Johnson, my arm is too short to box with God?

You have cast down the mighty from their thrones, *

and have lifted up the lowly.

When have I been one of the mighty cast down from my throne and when have I been one of the lowly that God has lifted up out of graciousness and compassion? Am I able to see that I can be both on a throne and lowly? Regardless my status, can I trust in God’s mercy and guidance and grow from the place in which I am and the place where I might end up?

You have filled the hungry with good things, *

and the rich you have sent away empty.

How have I, as a Christian, helped fill the hungry with good things? How have I helped bring about the great reversal of which Mary spoke, the turning-upside-down of the status quo so that reconciliation and restoration might come about? How have I, in Jesus’ name, worked toward the elimination of suffering and the advancement of peace, toward the creation of a world where the lamb shall lie down with the lion?

You have come to the help of your servant Israel, *

for you have remembered your promise of mercy,

The promise you made to our forebears, *

to Abraham and his children for ever.

Will I, with every breath I have, as long as I shall live, remember God’s promises and do my best to convey to others the good news of salvation?

+

Since we have four days this fourth week of Advent, and therefore a little time to rest with Mary’s song of praise, I encourage you to pray the Magnificat (canticle 3 and 15, found in Morning Prayer) these approaching days and then throughout the course of the year, examining your own heart in light of these prescient words. May it become a constant prayer of yours as it has for me.

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord; my spirit rejoices in God my saviour….

Even before spending fourteen-plus years at a church called Saint Mary’s, the Magnificat had a special place in my heart. More than twenty years ago at Trinity, Princeton, a small group of us used get together early Wednesday morning to pray Morning Prayer in Spanish. We always used to say the Magnificat because it seemed to connect us with the peoples of Central and South America and their struggles. Even now I can begin the Magnificat in Spanish — Proclama mi alma la grandeza del Señor…. Now, all these years and experiences later, the song continues to grow in its personal associations.

But, in fact, the Magnificat — a canticle that we say or sing usually at Evening Prayer, a hymn that one hears in a traditional Lessons and Carols on Christmas Eve — is a radical hymn. In one of those great paradoxes of our tradition, this hymn that is so well-known for its beauty is also underestimated for its force.

The Magnificat praises the power, the holiness and the mercy of God, the God whom Mary calls Lord and Saviour. It does not appear to tell her story, the one we so often hear of the young virgin who humbly and obediently submits to God’s desire that she be the bearer of the Son of the Most High.

Or does it tell her story? Does it give us a different picture of Mary, a picture often lost behind the imagery of a young girl, a virgin who knows her lowly place?

+

Only Matthew and Luke relate stories of the birth of Jesus, and only Luke tells us that Mary was actually informed of God’s intentions. Interestingly, after all the erudite language of the beginning of the gospel of Luke, when we get to the Magnificat, the language shifts — as though we were to go from using Elizabethan to conversational English. Also, unlike all the historical detail that we heard in the events surrounding the arrival of John the Baptist, historical accuracy is strangely lacking from Luke’s description of the encounter between Mary and Elizabeth. He moves from the realm of historical reporting to telling a story imbued with mystery and wonder.

As a sign that ‘nothing will be impossible with God,’ the angel Gabriel tells Mary about the pregnancy of her barren relative, Elizabeth. The angel departs, and Mary hurries off to Elizabeth, whose child, John the Baptist, leaps in her womb at the sound of Mary’s voice. Elizabeth blesses Mary as the mother of her Lord and for her faith in the truth of the message she has heard. Mary responds to Elizabeth with the words of the Magnificat: ‘My soul magnifies the Lord, and my Spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, for God has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant. Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed, for the Mighty One has done great things for me, and holy is God’s name….’

This rare New Testament psalm of praise can be divided into three parts: first, a personal thanksgiving for God’s actions for Mary; second, praise for God’s acts to all, and third, praise for God’s acts for the people of Israel.

Mary’s praise comes from deep within; her soul extols God her Saviour, the God who brings not only her but Israel out of bondage into right relationship with one another and with God. God the Mighty One will raise up those who are cast down and nourish those who are starving. She then considers God’s mercy — that loyal, faithful, gracious love that God has had in covenant with God’s people throughout time. The Magnificat itself is remarkable as a hymn of praise that is full of joy for God’s actions. It seems so fitting that the God-bearer, Mary, should be the one to proclaim these words even as she stands on the turning point of the ages.

+

The power of Mary’s words that always shake me to my roots and make me question how well I am doing as a follower of Jesus, her son. If I pray the Magnificat, verse by verse, and imagine myself in Mary’s place, how do these verses resonate within my heart? So, walk with me for a moment in a reflection on this hymn.

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour; *

for you have looked with favor on your lowly servant.

How well do I proclaim God’s greatness? Even in those moments of uncertainty, when it seems that God is asking me to do something impossible, when life seems to be asking too much of me, is my spirit able to rejoice honestly, openly, truly, thankfully in God my saviour?

From this day all generations will call me blessed: *

the Almighty has done great things for me, and holy is your Name.

How well am I able to acknowledge the great things that God has done for me, and praise God’s holy name? When things seem to be too much, am I still able to praise God? (I always think of the story of a homeless woman in Boston, who still prays every morning: Thank you, God, because I woke up this morning.)

You have mercy on those who fear you *

in every generation.

Do I recognise the mercy God has had upon me? How God has forgiven me the wrongs I have done, the wrongs I still do, and the pardon extended to me that will always be there even before I ask? Can I recognise that that same mercy is extended to others, even those with whom I am still not in right relationship? Can I give thanks that God’s mercy is there for all?

You have shown the strength of your arm, *

you have scattered the proud in their conceit.

How honest am I in acknowledging that I, too, am one of the proud? When do I need to be taken down a peg or two? When do I need to be knocked off my high horse of self-righteousness? When do I acknowledge that, in the words of James Wendon Johnson, my arm is too short to box with God?

You have cast down the mighty from their thrones, *

and have lifted up the lowly.

When have I been one of the mighty cast down from my throne and when have I been one of the lowly that God has lifted up out of graciousness and compassion? Am I able to see that I can be both on a throne and lowly? Regardless my status, can I trust in God’s mercy and guidance and grow from the place in which I am and the place where I might end up?

You have filled the hungry with good things, *

and the rich you have sent away empty.

How have I, as a Christian, helped fill the hungry with good things? How have I helped bring about the great reversal of which Mary spoke, the turning-upside-down of the status quo so that reconciliation and restoration might come about? How have I, in Jesus’ name, worked toward the elimination of suffering and the advancement of peace, toward the creation of a world where the lamb shall lie down with the lion?

You have come to the help of your servant Israel, *

for you have remembered your promise of mercy,

The promise you made to our forebears, *

to Abraham and his children for ever.

Will I, with every breath I have, as long as I shall live, remember God’s promises and do my best to convey to others the good news of salvation?

+

Since we have four days this fourth week of Advent, and therefore a little time to rest with Mary’s song of praise, I encourage you to pray the Magnificat (canticle 3 and 15, found in Morning Prayer) these approaching days and then throughout the course of the year, examining your own heart in light of these prescient words. May it become a constant prayer of yours as it has for me.

My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord; my spirit rejoices in God my saviour….

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Advent 3C

Every time I go to El Salvador, the earth speaks. Salvadorans like for the earth to talk; the more it does, the less they have to worry about some huge earthquake destroying their country. The capitol city, San Salvador, is called the valley of hammocks because there are so many earthquakes that the valley sways back and forth, gently and not gently, like a hammock.

Though I have felt little ones off and on, the one that sticks with me the most is one that woke me up in October 2005. I was on the fifth floor of a hotel in downtown San Salvador. It’s a concrete building, nothing elegant, but a homey place I like because I have stayed there over the years. I went to bed that night, and fell asleep quickly. But then, in the middle of the night, I heard creaking, lots of creaking. It took this New Englander a bit of time to realise that the creaking, coming from a concrete building, was the building swaying in an earthquake. Adrenaline shot up my spine, as it always does when I realise it is an earthquake waking me up, as though someone is viciously shaking my bed. I thought this time as I listened to the squeaking and creaking, ‘Well, if the hotel collapses, at least I am on the top floor.’

The earthquake quickly subsided. Later on the next day, when I checked with my Salvadoran friends if this was something about which I should have been concerned (I always want to make sure I am not being hyper sensitive about earthquakes), I learned that it had been a quake of 5+ degrees on the Richter scale and, yes, they felt it, too. It was a surprise gesture to wake me up. And it did!

+

This earthquake was so like John the Baptiser. He came shaking up things, shouting insulting words at the people, shattering the ways they normally thought about their world.

John’s ministry was meant to wake folks up. ‘You brood of vipers, sons and daughters of venomous snakes… who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?’ Off he goes on a verbal tear, excoriating those listening to him — not exactly what we would call newcomer welcoming. The gospel reading then ends with one of the most ironic lines to be found: ‘With other such exhortations,’ it says, ‘John preached Good News to the people.’ The same verb Luke uses to characterise the Baptist’s preaching is used later of the angel’s proclamation to the shepherds as well as at the end of Luke’s story when the risen Jesus tells the gathered disciples that ‘repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in Christ’s name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem.’ John is the precursor of much good news that will follow.

Today I want to preach some good news, hopefully in a less vitriolic fashion, but good news, which begins with hard news. The hard news is that to become open to the good news of God's love, to be prepared to welcome anew the Christ-child into our hearts, into our world, we have to deal with the reality that our hearts and world are unprepared and even closed for this gift.

+

Part of the preparation begins with repentance, that need to turn ourselves around so that we begin a different journey, a journey that finds energy and hope through forgiveness and rebirth, spiritually. We live in a time in which people are doggedly, earnestly plowing along on their ways, but without much hope, without much joy. Our journeys leave us empty of meaning and of happiness. We fill our days with busyness and with things we accumulate, to keep us from facing the hard truth, the truth that spiritually we are dry. We are wanderers, not pilgrims. And that realisation is difficult to acknowledge. How else do we understand the orgy this season of buying things, often beyond our means, if not that it is an expression of the passionate desire to love and be loved, as it tries to fill empty spaces in our lives?

Often it takes some earthquakes to wake us up, to remind us that there is something more to life, something more for which to journey.

How, then, is a call to repentance good news? How can a call to right living be heard as the gospel? For Luke, repentance and reformation are nothing less than what God has always wanted for human life. Right living is the only evidence of one’s trust in God.

So our question is, ‘Well, then, what should we do?

We can look at our lives and figure out how we can turn them around. Those places in our lives, those crooked, wandering paths of spiritual scoliosis that lead us up and down, in our relationships with one another, with the world about us, with God, — those are sites we must examine to see where we have gone astray. When we find the place that troubles us, we need to ask God’s forgiveness, the forgiveness of any of the parties involved, when possible, and of ourselves. Though we may fail again, we must try anew to follow the Great Commandment of loving God and neighbour alike.

How do we reform our lives? Of all times of the year, when the outside world is inviting us to spend beyond our means, when our schedules are leading us at a frenzied pace, it is so easy to lose sight of what this season is all about. It is about preparing our hearts expectantly, joyously for the coming of Christ, God’s ultimate spendthrift gift of love. We are invited during this season of preparation to look at our lives and see where our priorities might be out of whack with how we want to live our lives. Finding that, then we can try anew to have God at the centre of our lives with everything we do and are flowing from that centre.

What is right living for each one of us? Right living — something very difficult to do sometimes — is finding God in every one we meet, every one with whom we have a relationship. It is mending those places in our relationships that may have gotten a little frayed, a little torn. It is tending to those persons and places in our lives that need nurturing. It is respecting others and our selves. With God at the centre of our lives, we are given the strength and the wisdom to know how to do this — we need not be afraid, for God will show us how. We just need to trust.

A prayer from New Guinea says: Oil the hinges of my heart’s door that it may swing gently and easily to welcome your coming.

Yes, may those rusty hinges of your and my hearts’ doors, shaken up by the earthquake of the good news of reconciliation, burst wide open to greet the Christ child who is coming near soon…very soon.

Though I have felt little ones off and on, the one that sticks with me the most is one that woke me up in October 2005. I was on the fifth floor of a hotel in downtown San Salvador. It’s a concrete building, nothing elegant, but a homey place I like because I have stayed there over the years. I went to bed that night, and fell asleep quickly. But then, in the middle of the night, I heard creaking, lots of creaking. It took this New Englander a bit of time to realise that the creaking, coming from a concrete building, was the building swaying in an earthquake. Adrenaline shot up my spine, as it always does when I realise it is an earthquake waking me up, as though someone is viciously shaking my bed. I thought this time as I listened to the squeaking and creaking, ‘Well, if the hotel collapses, at least I am on the top floor.’

The earthquake quickly subsided. Later on the next day, when I checked with my Salvadoran friends if this was something about which I should have been concerned (I always want to make sure I am not being hyper sensitive about earthquakes), I learned that it had been a quake of 5+ degrees on the Richter scale and, yes, they felt it, too. It was a surprise gesture to wake me up. And it did!

+

This earthquake was so like John the Baptiser. He came shaking up things, shouting insulting words at the people, shattering the ways they normally thought about their world.

John’s ministry was meant to wake folks up. ‘You brood of vipers, sons and daughters of venomous snakes… who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?’ Off he goes on a verbal tear, excoriating those listening to him — not exactly what we would call newcomer welcoming. The gospel reading then ends with one of the most ironic lines to be found: ‘With other such exhortations,’ it says, ‘John preached Good News to the people.’ The same verb Luke uses to characterise the Baptist’s preaching is used later of the angel’s proclamation to the shepherds as well as at the end of Luke’s story when the risen Jesus tells the gathered disciples that ‘repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in Christ’s name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem.’ John is the precursor of much good news that will follow.

Today I want to preach some good news, hopefully in a less vitriolic fashion, but good news, which begins with hard news. The hard news is that to become open to the good news of God's love, to be prepared to welcome anew the Christ-child into our hearts, into our world, we have to deal with the reality that our hearts and world are unprepared and even closed for this gift.

+

Part of the preparation begins with repentance, that need to turn ourselves around so that we begin a different journey, a journey that finds energy and hope through forgiveness and rebirth, spiritually. We live in a time in which people are doggedly, earnestly plowing along on their ways, but without much hope, without much joy. Our journeys leave us empty of meaning and of happiness. We fill our days with busyness and with things we accumulate, to keep us from facing the hard truth, the truth that spiritually we are dry. We are wanderers, not pilgrims. And that realisation is difficult to acknowledge. How else do we understand the orgy this season of buying things, often beyond our means, if not that it is an expression of the passionate desire to love and be loved, as it tries to fill empty spaces in our lives?

Often it takes some earthquakes to wake us up, to remind us that there is something more to life, something more for which to journey.

How, then, is a call to repentance good news? How can a call to right living be heard as the gospel? For Luke, repentance and reformation are nothing less than what God has always wanted for human life. Right living is the only evidence of one’s trust in God.

So our question is, ‘Well, then, what should we do?

We can look at our lives and figure out how we can turn them around. Those places in our lives, those crooked, wandering paths of spiritual scoliosis that lead us up and down, in our relationships with one another, with the world about us, with God, — those are sites we must examine to see where we have gone astray. When we find the place that troubles us, we need to ask God’s forgiveness, the forgiveness of any of the parties involved, when possible, and of ourselves. Though we may fail again, we must try anew to follow the Great Commandment of loving God and neighbour alike.

How do we reform our lives? Of all times of the year, when the outside world is inviting us to spend beyond our means, when our schedules are leading us at a frenzied pace, it is so easy to lose sight of what this season is all about. It is about preparing our hearts expectantly, joyously for the coming of Christ, God’s ultimate spendthrift gift of love. We are invited during this season of preparation to look at our lives and see where our priorities might be out of whack with how we want to live our lives. Finding that, then we can try anew to have God at the centre of our lives with everything we do and are flowing from that centre.

What is right living for each one of us? Right living — something very difficult to do sometimes — is finding God in every one we meet, every one with whom we have a relationship. It is mending those places in our relationships that may have gotten a little frayed, a little torn. It is tending to those persons and places in our lives that need nurturing. It is respecting others and our selves. With God at the centre of our lives, we are given the strength and the wisdom to know how to do this — we need not be afraid, for God will show us how. We just need to trust.

A prayer from New Guinea says: Oil the hinges of my heart’s door that it may swing gently and easily to welcome your coming.

Yes, may those rusty hinges of your and my hearts’ doors, shaken up by the earthquake of the good news of reconciliation, burst wide open to greet the Christ child who is coming near soon…very soon.

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

More snow photos!

Today's snow storm slowed things down but did not shut down the church.

Chapel entrance

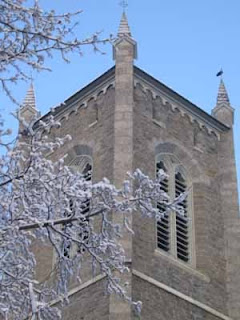

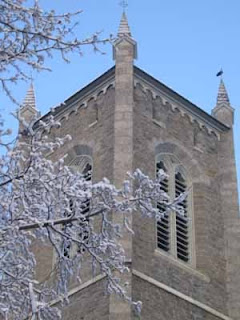

Main tower in the snow

Far right door which used to lead into the 'war chapel,' that is, a space open for prayer during WWII (if I have that correct)

East side with memorial garden

Inside the chapel ready for the Wednesday noon Eucharist

Chapel entrance

Main tower in the snow

Far right door which used to lead into the 'war chapel,' that is, a space open for prayer during WWII (if I have that correct)

East side with memorial garden

Inside the chapel ready for the Wednesday noon Eucharist

Monday, December 7, 2009

Advent 2C

Advent 2C • 6 December 2009

Have you ever been on the highway in a snow storm when the snow is coming down hard, hard and someone goes barreling by you, churning up an egg-beater type cloud of snow, so dense that for a few minutes, you can’t see anything at all? And you are in one of those moments of driving blind, not having any idea where you are on the road, where the edge of the road is, whether you are going up or down or whether you’ll emerge from the cloud intact? This feeling is frightening and sometimes awesome. It almost certainly reminds me of my fragility and smallness in creation and how much I need to depend on God. That’s one way of experiencing wilderness, Vermont-style, even if it is created by the confluence of weather and human behaviour.

But then there’s the real wilderness, the desert (which, in the time and place of the writing of Luke’s gospel, were fairly synonymous). Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, in Night Flight, wrote so beautifully of the desert in evocative and eloquent words, depicting its stillness, its coldness in the middle of the night… and the isolation and desolation so often felt there.

A more contemporary writer, Rabbi Michael Comins describes the desert thusly:

First and foremost, the desert is a dangerous place. Like Hagar or Elijah, you can easily lose the way, finish your water and find yourself facing collapse in a few short hours. Or you might fall prey to desert bandits. To be in the desert is to lack personal security.

The word for the desert is extreme. Since there are seldom clouds to block the sun during the day or hold the heat at night, and moderating oceans are far away, thirty and forty degree temperature swings are the norm. If the day is pleasant, the night is too cold. If the night is temperate, the daytime heat will melt your candy bar, and perhaps your equilibrium. Light is too intense for comfort. The sun blinds, dehydrates, kills. You’ll never see a Bedouin resting in the sun.

In the desert, you get down to essentials. Water, shade and a bit more water. The body wants little food. A heavy pack draws moisture from your body, which evaporates so fast, you might not even notice that you are sweating.

The desert, in short, is a place where people are tested physically, and thus spiritually. If you don’t know which canyons still have pools from the last rain or the secret water holes of the desert people, hope and confidence evaporate.

The desert can be mentally trying even when the body is not under duress. Quite often the horizon is a straight line. Indistinguishable washes, endless plains, the hot wind. Nothing to cling to. Nowhere to go.

Infinite space; infinite fear.

***

And infinite possibility. The only center is the center within, and so one looks inward. The desert is a place to become as straight as the horizon, as sharp as a thorn. Learn to live with little. Learn to live in light so bright that nothing in your soul can remain hidden. Learn to live at risk.

The contract reads: courage required.

No exceptions.

***

The truth is that life everywhere is just as extreme as it is in the desert. Only we do our best to believe that it isn’t, and in civilization, we can easily delude ourselves into thinking that we’re getting away with it.

The desert does not indulge those who cannot tell reality from a mirage. …Pretense is not an option.

The desert is one of God’s most precious gifts.

+

It is into this sort of environment that I imagine John the baptiser wandering. And it was this sort of inner introspection and searching in which his call to repentance invited followers to engage. John’s words of repentance would have been familiar to his listeners—there was the daily changing one’s mind, understood either by the Hebrew shuv or the Greek μετανοια. But, in the religious context, the words took on the meaning of ‘broadening the horizons, transformation of experience, reform of life.’ In the Judaic mind, which would have been that of John’s time, though not necessarily that of the gentile audience the writer of Luke’s gospel intended, turning to God meant turning away from ways that are disobedient or displeasing to God. By turning to God, the person would obtain forgiveness of sins. John does not explain clearly what he means by this forgiveness, but a close analogy would be ‘forgiveness of debts.’ Any peasant would understand that notion since they lived in debt all the time. By turning to God, one might just have those debts forgiven.

John quotes Isaiah 40.3-5, yet another sign of his serving as a transitional figure between the Hebrew prophets and the new prophet, Jesus the Christ. He speaks of straightening out crooked (the Greek being scoliosis, a word we know from bent spines) roads, making new what was old. More important, however, is the continuation of a pattern common in Luke, where he introduces a phrase from the Hebrew Scriptures with the anticipation that its meaning will be fulfilled by Jesus. In this case, Luke uses Isaiah to anticipate Jesus as the saviour who will bring people out of their exile. The way people will be brought out of exile, be it the spiritual wilderness or desert or any other form of exile, is through God’s intervention. God will clear away all the obstacles in the way of God’s people, particularly the low and humble. But to be a part of this path, one must be ready of heart.

We normally think of Lent as our time of journeying in the desert or wilderness. That it is. But Advent, even with its emphasis on preparation and celebration, also invites us to those rough places in our lives, where the roads are very crooked.

It takes courage to set off on a journey to the desert, especially the desert of the heart and soul. It takes courage to be baptised in the waters of life because by so doing, we are affirming that we will embark on a life-journey of repentance and forgiveness of sins. Much of our life may be spent in the desert, where living does not come cheaply.

Today we will be baptising (at the late service) three people, Leah, Michael and Isabella, two youth and an infant. We will be launching them on this journey to the desert and beyond. It is an awesome, fearsome event, but one that is done in community with all of our help and guidance.

No matter how awesome and fearsome the spiritual vastness of the wilderness or the desert might seem, we must trust that God is walking with us, carrying us when necessary, and making clear the path. No matter how much gets churned up in front of us, obscuring our vision, we must remember the gift of reconciliation and forgiveness that has already been given to us.

John the baptiser has called us today to set off on our journey, to repent, to turn anew to God, and to live without pretence. There’s not much time between now and the nativity of our saviour Christ, so we’d best be on our way.

++++

Michael Comins, ‘The Spiritual Desert,’ www.torahtreks.com.

Snowy Second Sunday in Advent

Here are a few photographs taken quickly before the 8.00 service yesterday morning.

Strategically placed so as to avoid the spotlight in the foreground.

'Open the doors of righteousness....' (Psalm 118)

Trinity turrets

It's a little unclear but that is a big crow up on the right-hand cross of the tower.

The Episcopal Church Welcomes YOU!

Strategically placed so as to avoid the spotlight in the foreground.

'Open the doors of righteousness....' (Psalm 118)

Trinity turrets

It's a little unclear but that is a big crow up on the right-hand cross of the tower.

The Episcopal Church Welcomes YOU!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)